When in the early planning stages of opening a brewery, I have found a lot of folks make detailed spreadsheets to figure out the seating capacity, table turn and how many beers per seat, per hour, to come up with an estimate of daily sales.

However I would like to offer a different perspective in your planning: figure out what it costs you to be open in the first place. To do this let’s look at some key concepts.

Prime Cost

This is the large cost to produce what you sell. It not only calculates the cost of ingredients but also the labor to produce it. For example I would on a spreadsheet calculate an IPA recipe and include all the cost of ingredients (except water - I don’t need that much detail!). It might come in around $50 per keg because it’s a high gravity beer with a whole lot of hops. Then I would look at the labor. You could do that in a couple ways. If the brewer is hourly, just add the hours not only for the brew, but for the transfer, kegging, tank cleaning, TTB reporting and anything else involved. An even simpler way would be to look at the cost of the brewer for the month and how many barrels produced to come up with a labor per barrel or labor per keg cost.

With this information you can come up with the cost per pint then divide that by how much you are going to sell the pint for and this will give you your optimum %, or cost of sale you are shooting for. This would be your prime cost for that pint. It could be in the range of 12% to 20%, depending on your efficiency and what you pay your brewer. So that means it would cost you roughly .12 to .20 for every dollar you bring in to pay for the beer.

Nut

This is what your space cost you no matter how you run it. The main one here is your rent or mortgage payment for the space. The next is your bank loan. As I’ve said in the past, try to get your rent or mortgage to 7% of your monthly sales or less. You could go as high as 10%, but anything more than that and you are working for your landlord. For example if my rent was $5,000 and I wanted that rent to be 7% or less than I would need a monthly gross sales of $71,428.71. Take your rent and divide by .07. Now it makes sense to figure out how many pints you need to sell, along with food, wine, merchandise, etc. to come up with those sales.

The other part of the nut is your bank loan. This is why I recommend if you are doing a brewpub to take over an existing restaurant, because most of the infrastructure is already in place and you will -hear me now or believe me later - save buckets of time and money. In fact these days there are actually breweries (brewpubs and even tasting room and packaging breweries) that have gone out of business, and those spaces could be available for purchase or rent and are already built out. When I say built out, it means they already have floor drains, up to code restrooms, parking, offices, heating and air conditioning in place. These are all the things that are so damn expensive and your customers don’t even see them. This leaves you with extra money you can spend on things your customers will see. All the cool decorations and such.

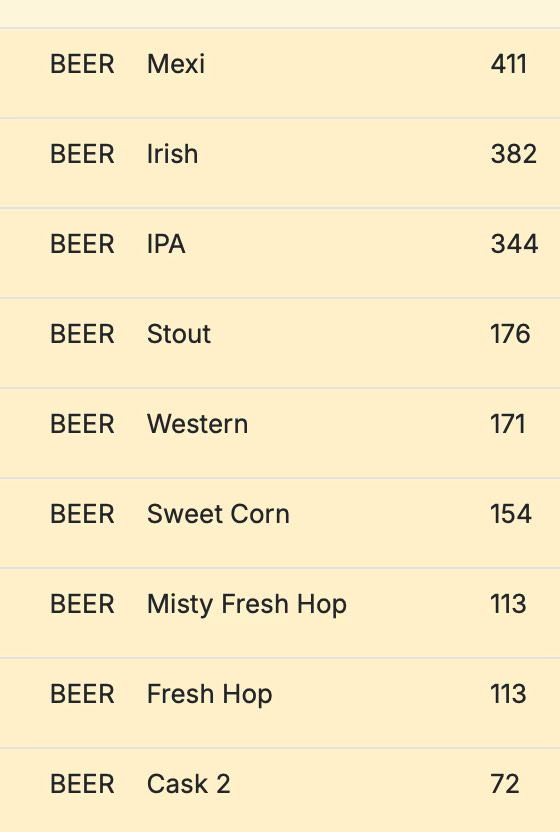

80/20

Perato’s rule that 80% of your gains come from 20% of your efforts. This is super powerful, especially if you’ve been in business for a while, so it pays to have another look at this. You need a POS system that tracks sales by item. It will spit out a report of what items sold according to volume. This is important to see what sells the most. Now go back to your prime cost and figure that in as well. You may find items that cost you a whole lot to produce but don’t sell as well as the ones that are relatively inexpensive to make but sell super well. Those are the items to push, and the ones that are dogs, just jettison them.

If you are a packaging brewery, you will find this very enlightening when you compare the prime cost of your package sales to sales volume, against your tap room sales and prime cost. It may make you re-examine whether you want to be canning or doing packaging at all.

I know this is all dry and un-sexy, but it is the foundation of your business plan. If you have a handle on these three things, and you happen to make great beers in an attractive setting with good systems, you should thrive. I would venture to guess that those breweries that didn’t make it, had issues along these lines. So even their stellar beers couldn’t overcome bad prime costs or their nut.

Thoughts??

Well said. The breweries I’ve financed and consulted with usually get in trouble with the “nut”. Also ego of the brewer/owner is a problem. I always recommend a tiny board of directors made up of business people the owner trusts to guide decisions of the owner is also the brewer.