Keep Your Head

It can't just taste great

A typical question most brewers get from non-brewers is, “what’s your favorite beer?” When I started brewing, it was the hoppiest thing I could get my hands on. I remember speaking to Bert Grant, of Grant’s Ales at a Great American Beer Festival in the ‘90’s. He brought a beer called, Hopzilla. It could rip the enamel right off your teeth. I thought it was wonderful.

My tastes have changed and now what I am looking for is no off-flavors, clear beer (if that is the style) and head retention. I just marvel at a properly crafted brew with thick, dry, tight foam that laces all the way down the glass as you sip. So in this newsletter I would like to talk about achieving this miracle without getting too wonky about long protein chains and polyphenols. Rather, some simple steps you can use to make a beer look like a beer should, rather than flat piss in a toilet.

Carbonation

First you need to carbonate your beer properly. What is that you say? It’s having a proper amount of CO2 volumes per liter, which will be your first stop on the road to better head retention.

We have a Zahm Nagel CO2 tester, so we can hit it exactly - when we actually use this expensive device. If you are packaging you are looking at about 2.5 to 2.7 volumes of CO2 per liter. We strive for a little less, because we don’t want to waste a lot of beer at the taps filling growlers and pints, so for us, 2.4 seems reasonable.

While a Zahm Nagel is the industry standard bearer, there are others that are much less expensive, like the Taprite system, which runs in the $350 range. If you start hitting your target CO2 volume levels, you will be way ahead of your brewery competition most likely. Many brewers carbonate by feel. You’ve carbonated so many times that you have a pretty good idea what your carbonation will be. However, without testing, you are still flying blind because the gravity of the beer has to also be taken into effect.

Glassware

It is no surprise that you need to start with a clean glass, but what are you cleaning the glass with? You want to avoid household soaps, which can leave a film that prevents foam from clinging to the glass. There are commercial bar glass cleaners and sanitizers made for three-compartment sinks available from your distributer that will do a good job.

Equally important (or more) is the shape and type of glass you are using. Personally I can’t stand beer in a straight sided shaker style of glass like the one pictured above. All they have going for them is they are cheap to buy. But when you consider all the money spent to build your brewery, and all the talent and energy you put into creating that great beer, why put it in a cheap glass. For our purposes here, we want a glass that narrows a bit at the top. This helps greatly in maintaining a head of beer, by limiting the exposure of foam to air. Try pouring your beer in a shaker pint, and also a snifter or a tall pilsner glass and see what I mean.

We use English pint glasses with the bulge in the side, and then it narrows at the top. However we serve all our lagers in a tall, skinny 16 oz. glass, and you can always see the lacing all the way down to the bottom. The French say we eat with our eyes, but I say we drink with them too. Glassware makes the experience that much more memorable.

Malt

I think most of you know this already, but by adding more dextrin to your grain bill you will increase your head retention. Carapils, wheat malt, or flaked barley can be added up to 5% of your total grain, however if you go much further it could also effect your flavor profile and your clarity. That being said, my old IPA recipe had 7% carapils in it and it won gold at the world beer cup (1996, not a lot of competition compared to today).

The other thing you can do is to raise your mash temperature. I’m assuming most of us are using modified malts and there will be no step-infusion mash. I would typically mash in at 153 F, but I have read that 155 to 160 will work. I have never gone that high on a mash - on purpose - but I’m willing to give it a try.

Yeast

Those German and Belgian beers don’t have a stiff head just because of the glasses they use. Their yeast selection is a huge. contributor to head retention. Many Belgian and German strains of yeast actually produce less fusal alcohols, which can reduce foam stability. You might want to include head retention when looking at yeast selections.

Proper mash pH is also vital. I tend to follow my yeast hero, Chris White, who seems to think 5.3 is the Goldilocks target. Proper head retention can’t happen without proper fermentation, and yeast are happiest in the 5.0 to 5.5 range. I piss off a lot of people, but I never want to piss off my yeast.

In addition to pH, having enough oxygen for the little yeasties is also vital. Use a oxygenating stone and straight oxygen flowing at about 4 to 5 liters per minute. Your target is 10 parts per million of dissolved oxygen. Without a dissolved oxygen meter you don’t know for sure, but at 4 to 5 ppm, I think you would get there. I’m sure I will hear from some of you about your experience.

Healthy yeas is extremely important as well. I’m talking about pitching an adequate amount of yeast for the type of beer you are brewing. For example, if you buy a pitchable amount of yeast for a seven barrel batch, that yeast you receive is really only adequate for a beer that is 7 degrees Plato. There aren’t enough yeast cells for a seven barrel batch of Irish Red at 13P. To get around this, when we get new yeast, we make sure we have two fermenters available. When transferring our seven barrels from the heat exchanger, we first transfer about two and a half barrels into one fermenter with the new yeast, then the remainder of the wort into the other fermenter with the old yeast. That way when the beer is finished, we transfer from both fermenters, but harvest just the new yeast, which is in perfect health, having not been stressed by too much wort and not enough yeast cells. There will also be plenty of this yeast for a full batch of whatever we want to brew next.

Finally, I recommend you do yeast cell counts with every brew, which only takes about five minutes. Here is a video on how to do to it. That way you know how much yeast you have (cells per ml) so that you pitch the proper amount of yeast for your next brew based on that beers gravity.

Once Again:

No household soaps to clean you glasses

Use glassware conducive to better head retention

Add some wheat malt of flaked barley (up to 5%) of your grist bill

Up your mash temperature from 155 to 160 when appropriate

Experiment with yeast strains better suited for foam stability

Use enough yeast for the gravity of the beer you are brewing

Aerate your wort for a healthy fermentation

One final thought. When you are having a beer, slow down. Let the beer sit in front of you for a minute or two before you take that first sip. In that time the head will stiffen up, and you will not only get a better lacing, but your beer will be so much more enjoyable with a foam mustache.

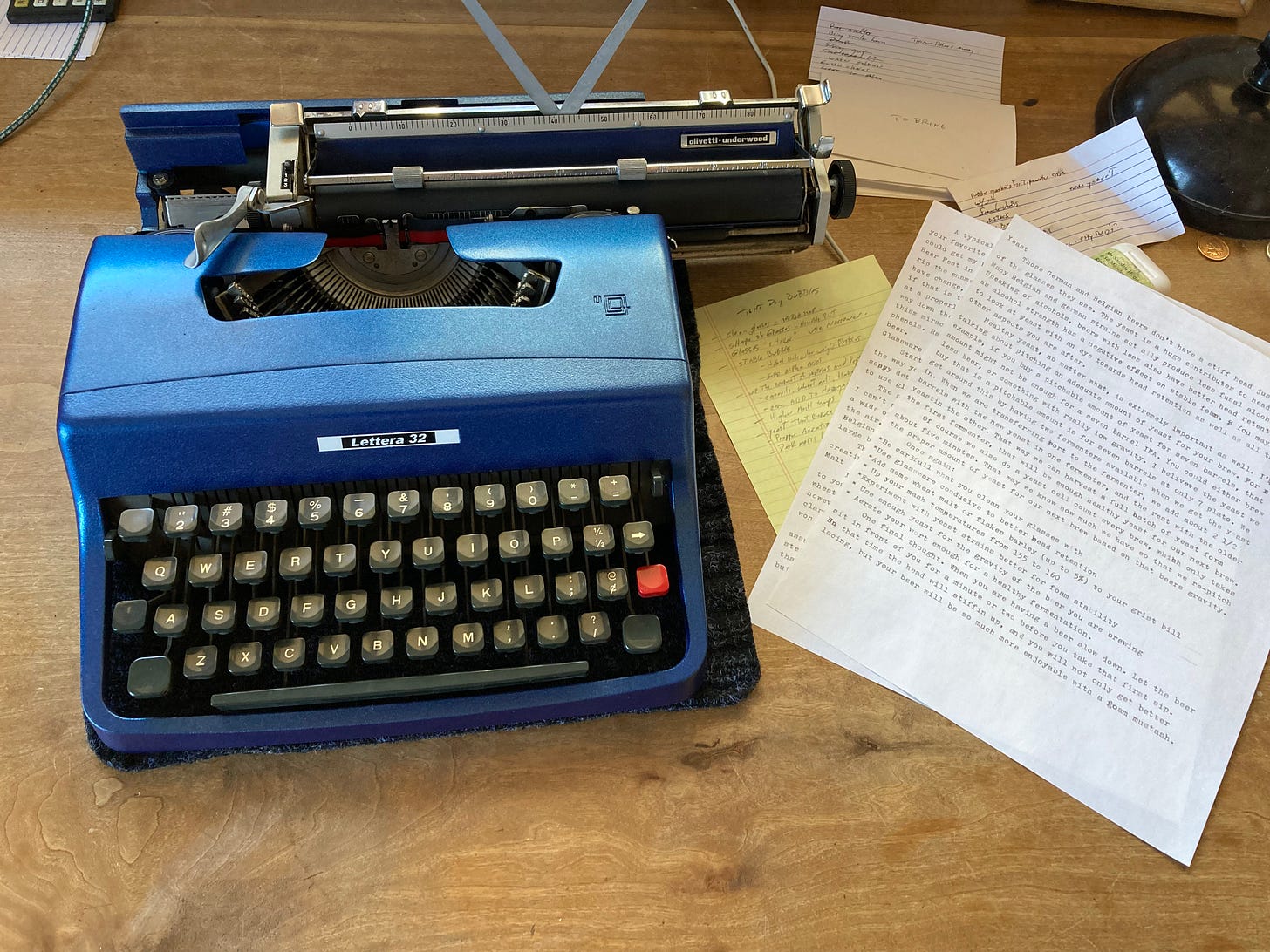

The draft (no pun intended) of this was typed on a 1965 Olivetti Lettera 32.